A recent paper in the applied linguistics journal System, compares the practices and beliefs of twenty-eight lecturers at ten European universities with the corresponding university language policy documents. The twenty-eight lecturers in the study came from the following six countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Spain and Sweden. They were all attending an online, in-service professional development course called Two2Tango. The goal of the course was to encourage transnational collaboration within EMI. Six of the twenty-eight participants in the study were Swedish (from Chalmers and Karolinska Institute). In the course, participants from two European countries were required to work together in pairs over the asynchronous virtual platform Canvas. In total, forty teachers from nineteen different academic disciplines participated, with those who completed all assignments on time invited to be included in the study. All teachers were proficient in the English language, ranging from B2 to C1 on the Common European Framework (Council of Europe, 2001).

In the course, participants completed assignments based around discussing their personal approach to EMI and any issues they had encountered along the way. The raw data for the policy/practice comparison came from two sources:

- Each participant’s online postings.

- The corresponding language and internationalization policies as sourced from their university website.

Six of the universities had formalized internationalization and language policies, whilst the other four only had descriptive web pages.

The source texts (central policy documents and the corresponding participant’s online postings) were provisionally coded in NVivo and three overarching themes were identified:

- The role of academic languages in internationalization

- Institutional measures

- Pedagogical approach

Thereafter data were separately coded manually by the two authors and qualitative thematic analysis was carried out—see for example Braun & Clarke, (2006).

The university policy documents raise topics such as international collaboration, raising quality and international impact/ranking. Chalmers, for example, justifies EMI on the grounds of the international impact of their research. This is not something that is mentioned by lecturers. Three of the ten universities express concern about the use of L1 in an academic context in their policy documents. Here, Copenhagen discusses the concept of parallel language use (see also the Stockholm University language policy). This issue was also mentioned by six of the lecturers in their communications.

A number of policy documents detailed incentives for lecturers to engage in EMI—reduced workload and merit for promotion for example. These initiatives were largely ignored by lecturers in their online discussions.

Surprisingly, only three universities specified the level of English language needed in order to teach in English (Ghent, Copenhagen, Madrid). Here Copenhagen is leading the way having created an EMI lecturer accreditation scheme—Test of Oral English Proficiency for Academic Staff (TOEPAS). Discussions of pedagogy were almost completely absent from the central policy documents.

In contrast, the lecturers mainly discussed pedagogical problems faced in EMI, such as issues of assessment of disciplinary learning when students have poor English language skills. Here, some of the main research themes in EMI came to the fore, such as the valuing of (disciplinary) communication over linguistic accuracy and lecturers’ unwillingness to correct English language mistakes. In contrast to the policy documents’ focus on incentives, lecturers criticized the lack of training for EMI teaching. All lecturers emphasised the importance of English for their students in order to communicate in an international globalized society. On the whole, lecturers did not discuss EMI in terms of raising the academic standing of the institution or the quality of the students they attract.

Comment: There has been a great deal of research carried out into teaching in English at university level, but there are three factors not explicitly discussed in this article that affect disciplinary language use that I think readers should be aware of.

First, the general level of language competence in society has a large effect on the use of English in a country’s universities. Here, there is a north/south divide in Europe, with Mediterranean countries generally having much lower levels of English language competence in society than Northern Europe. The Nordic countries and the Netherlands have the highest levels of English language competence in society and have also consistently topped the league tables for the amount of EMI in their tertiary education (Wächter & Maiworm, 2014). This is one of the reasons that findings in one country may not unproblematically transfer to another country.

Next, issues of language and power are important. Smaller language communities and countries where there is a feeling that the language is under threat are more likely to contemplate the effects of EMI on the ability to discuss disciplinary ideas in the official first language(s) of the country. This often results in policy statements about the development of L1 academic language. A case in point can be seen in Stockholm University’s own language policy where parallel use of English and Swedish is specified. Here we can see a tension between the desire to internationalize and the long-term viability of Swedish as a disciplinary language.

Finally, the discipline in which the research has been carried out is important. Attitudes to language are quite different across disciplines, with sciences generally viewing language as a passive encoder of knowledge, while humanities view language as the way in which knowledge is created and disputed. In the words of Halliday and Martin (1993: 8)

Language is not passively reflecting some pre-existing conceptual structure,

on the contrary, it is actively engaged in bringing such structures into being.

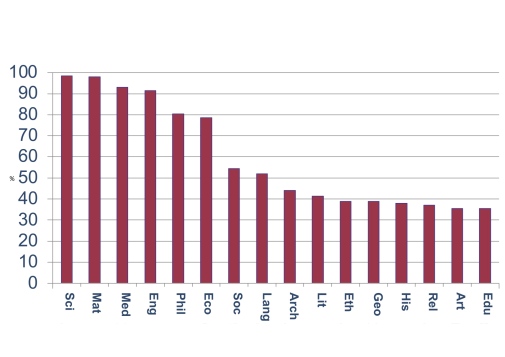

This pattern can be seen in the frequency of English language use within disciplines. For example, Salö (2010) collated the percentage of Swedish PhD theses that were written in English:

Swedish PhDs written in English 2008

Here, we can clearly see disciplinary differences, with sciences at one end of the scale and humanities at the other. It would, of course, be interesting to see how the pattern has changed over the last 15 years!

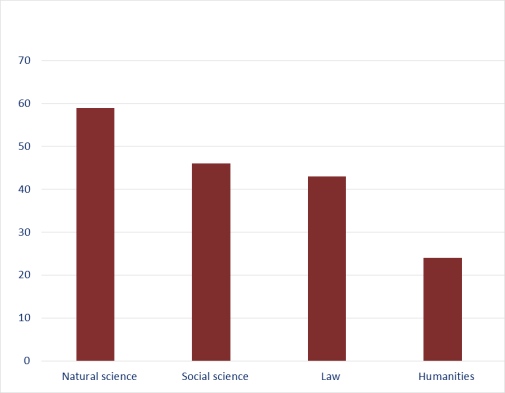

Similarly, a survey of EMI teaching conducted at Stockholm University (Bolton & Kuteeva, 2012) found the following percentages of lecturers describing themselves as giving either all or about half of their lectures in English.

Lectures given in English at SU (all or about half)

The important point here is that attitudes to English are not entirely the product of different disciplinary traditions, but are also a product of ontological and epistemological differences in how knowledge is viewed. Writing with colleagues from the Nordic countries in the journal Higher Education, we have discussed these issues (Airey et al. 2017) pointing out the potential pitfalls of one-size-fits-all university language policies.

Text: John Airey, Department of Teaching and Learning

Keywords: English Medium Instruction, Language policy, Internationalization

References

- Airey, J., Lauridsen, K. M., Räsänen, A., Salö, L., & Schwach, V. (2017). The expansion of English-medium instruction in the Nordic countries: Can top-down university language policies encourage bottom-up disciplinary literacy goals?. Higher education, 73, 561-576.

- Bolton, K., & Kuteeva, M. (2012). English as an academic language at a Swedish university: Parallel language use and the ‘threat’of English. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(5), 429-447.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Martin, J. R. (2003). Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. Taylor & Francis.

- Salö, L. (2010). Engelska eller svenska?: en kartläggning av språksituationen inom högre utbildning och forskning. Institutet för språk och folkminnen.

- Wächter, B., & Maiworm, F. (Eds.). (2014). English-Taught Programmes in European Higher Education. The state of play in 2014. Lemmens Bonn.